In his book “The Quest to Know the Human Heart: The Disruptors Who Created Modern Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery,” Dr. Stephen B. Guss argues that the science of the heart, its diseases, and their treatment did not progress logically in a straight line. Knowledge advanced through a struggle between “disruptors” challenging accepted “truths” and “restrainers” loathe to give up established beliefs. Restrainers sometimes prevailed for decades or even centuries. Dr. Peter Rentrop, whose contributions to the understanding of heart attacks Dr. Guss features, reviews the circuitous path to effective treatment of this number one killer in our society.

The culprit of a heart attack, as is widely known, is a blood clot (thrombus) that obstructs one of the heart’s arteries (coronary artery). The thin inner lining of arteries, called “intima,” can tear where it covers an atherosclerotic narrowing (plaque). Blood enters ruptured plaques and clots, sealing the tear. Excessive clot formation can obstruct a narrowed artery completely.

The sudden cessation of blood flow results in the death of the downstream heart muscle heart attack.

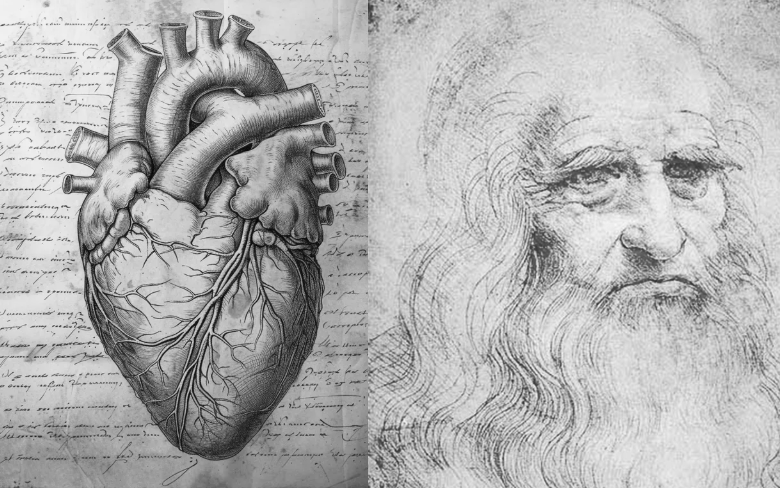

The first traces of this concept appear seemingly out of nowhere with Leonardo da Vinci in the 15th century. Medical thinking was still ruled by Galen of Pergamum, a Greek physician born in 129 CE, famous for treating gladiators and Roman Emperors. Galen taught that blood was produced by the liver, from where it reached all tissues on a one-way trip through veins to be absorbed as nourishment. Galen did not realize that the heart was a muscle, let alone the pump in a closed circulation.

The first traces of this concept appear seemingly out of nowhere with Leonardo da Vinci in the 15th century. Medical thinking was still ruled by Galen of Pergamum, a Greek physician born in 129 CE, famous for treating gladiators and Roman Emperors. Galen taught that blood was produced by the liver, from where it reached all tissues on a one-way trip through veins to be absorbed as nourishment. Galen did not realize that the heart was a muscle, let alone the pump in a closed circulation.

Over a millennium later, Leonardo concluded from his autopsies that the heart is a muscle with four chambers. He understood that the heart muscle is nourished by blood flowing through the coronary arteries. He was the first to identify coronary artery disease when he described coronary artery narrowing resulting from intimal thickening, which he attributed to “excessive nourishment” from the blood. Leonardo kept his numerous medical drawings and observations from the public until his death in 1519. It has been suggested that he feared the Inquisition with its intolerance for new ideas.

In 1764, the English physician William Hunter gained access to Leonardo’s drawings and notes, but the medical community was not interested in them. Coronary artery disease had to be rediscovered.

When William Heberden introduced the term “angina pectoris” in 1768, he did not know its cause. Ten years later, Edward Jenner, famous for smallpox vaccination, described in a letter to Caleb Perry the hardened and obstructed coronary arteries his scalpel encountered at autopsies of patients who had suffered from angina. He realized that angina symptoms indicate coronary artery disease.

Astute observations such as Jenner’s were not sufficient to unravel the causes of acute myocardial infarction. Rudolph Virchow, born in 1821 in Prussia, developed the methods needed: systematic observation, experimental pathology, and Cellular Pathology. The latter postulates that all diseases are based on structural impairments of cells, elevating the microscope to the pathologist’s most crucial tool.

Virchow studied the cells in atherosclerotic plaques and blood clots, both central to our understanding of myocardial infarction. His conclusion that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory

process, which was rejected for over a century, guides current research. He coined the term “thrombus” to denote a blood clot located at its origin and “embolus,” a clot that has traveled from another site, and showed that blood clots in the lung are emboli broken off from thrombi in veins.

Julius Friederich Cohnheim, Virchow’s chief assistant for three years and then head of his famous laboratory of experimental pathology, published 1872 his “Studies on the Embolic Processes “. He showed that abrupt obstruction of an artery by a blood clot in an organ causes tissue death, i.e., infarction, if the obstructed artery is not connected with neighboring arteries. However, if neighboring arteries provide blood flow to the obstructed vessel through connections called “collaterals,” tissue damage can be limited or even prevented. Cohnheim’s declaration that human hearts are devoid of collaterals initiated a long-lasting controversy (which led Dr. Klaus P. Rentrop to develop his collateral classification in 1985).

New dyes developed by the German chemical industry in the 1870s attracted the attention of Karl Weigert, also a student of Virchow and then Cohnheim’s assistant. With novel staining techniques still used today, he improved the analysis of tissue and cell structures. The first microscopic analysis of infarcts of the heart is found in Weigert’s 1880 landmark paper “Über die pathologischen Gerinnungsvorgänge.” In fact, the term myocardial infarction (“Infarcte des Herzmuskels”) appears here for the first time. Weigert’s key statements are translated from the original German by Klaus Peter Rentrop, MD. Myocardial infarcts look like “yellowish dry masses quite similar to clotted fibrin.” However, microscopically, they appear “like normal tissue (sometimes one even recognizes the cross-striations of the muscle fibers); however, all muscle fibers and all connective tissue lack nuclei.” Loss of nuclei proves cell death.

Weigert saw these changes only after ”…an abrupt, complete cutting off of the blood supply..”, not after gradual occlusion or if collaterals provided residual blood flow. What blocks blood flow abruptly? “Thrombotic or embolic occlusions of branches occur not infrequently at the site of atheromatous changes of coronary arteries. “ Here, Weigert has identified for the first time the cause of acute myocardial infarction: a blood clot that occludes an atherosclerotic coronary artery.

Weigert’s conclusions, based on a careful and complex scientific study, not just some isolated observations at autopsy, have been ignored, plagiarized, and rejected, but stood the test of time and eventually led to modern infarct therapies.

Carl Huber published the patients’ clinical histories in Weigert’s infarct study in 1882. Clinicians, however, paid little attention to Weigert’s insights for almost 40 years. Myocardial infarction is difficult to diagnose because its symptoms vary greatly. Furthermore, Cohnheim’s animal experiments suggested that it was nearly always rapidly fatal.

However, reports of survived myocardial infarcts appeared. Potentially protective collaterals were documented in humans. In 1912, James B. Herrick reviewed this primarily German and Austrian research (overlooking Weigert), added his own experience, and pronounced excitedly to North American Internists that myocardial infarction is caused by a thrombus and is not invariably fatal. He evoked little interest.

Herrick then addressed the problem of diagnosing infarction. In animal studies, he explored the electrocardiogram, which was used primarily to assess irregular heart rhythms at that time. In his 1919 paper “Thrombosis of the coronary arteries,” Herrick added serial electrocardiographic changes in three of his infarct patients to a presentation of the same concepts he had published in 1912. This time, clinicians were galvanized. The electrocardiograms up to 178 days after the event demonstrated that heart attacks are not invariably immediately fatal. Electrocardiographic changes enabled physicians to establish the diagnosis objectively. Clinicians began to think about therapies, and new fallacies would arise. Stay tuned for the next chapter.